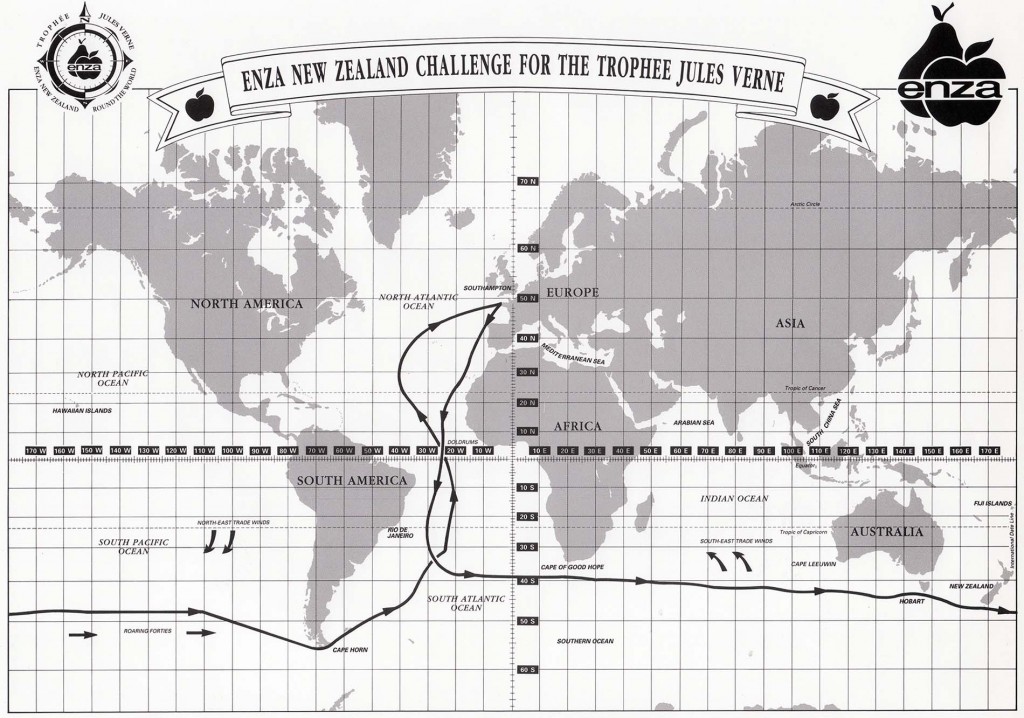

Forced to abandon their attempt in 1993, Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston were back to try their hand at the Jules Verne Trophy in 1994. Their catamaran, ENZA New Zealand was now rated the world’s largest racing sailboat. On board this new prototype, with a crew of eight, Blake and Knox-Johnston prepared to set a new record for the Jules Verne Trophy.

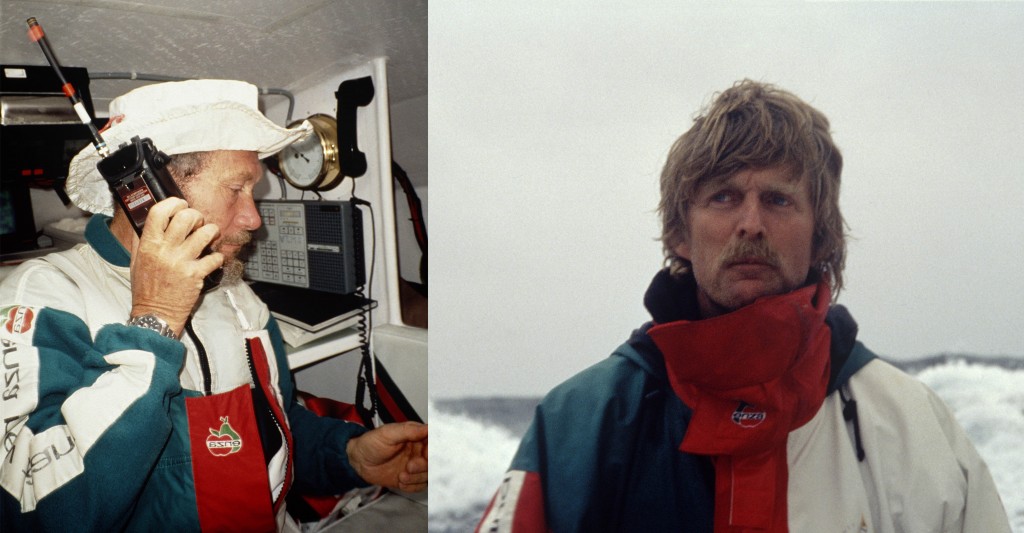

A 35-knot (65km/h) northerly wind was beating up foam off Ushant, on 16 January 1994(1)(1)Beyond Jules Verne, circling the world in a record-breaking 74 days, Robin Knox-Johnston, Hodder and Stoughton, 1995.. Peter Blake was at the helm. At his side, Robin Knox-Johnston was smiling despite the cold and sea spray. At 14 hours and 5 seconds, the catamaran ENZA New Zealand had just crossed the starting line of the Jules Verne Trophy, its mainsail reefed and its genoa maximized, flirting with a speed of 20 knots.

Already, the memory of ENZA painfully heading back towards South Africa was distant. Yet it was less than a year ago that the New Zealander catamaran, 26 days into its Jules Verne Trophy assault, had collided with an unidentified floating object. The dual of the giants being played out on water from Ushuant came to a brutal end at the time.

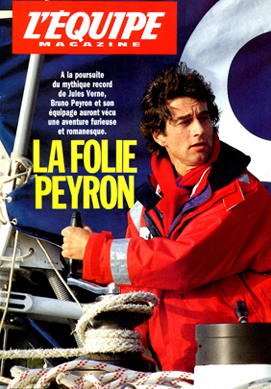

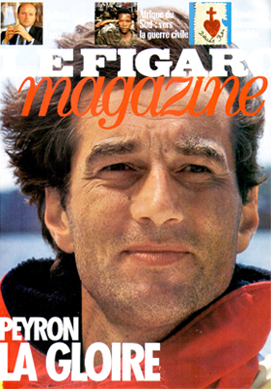

Bruno Peyron, on board Commodore Explorer, would continue on his way to snatch the round-the-world record at 79 days, 5 hours, 15 minutes, 56 seconds… And to carry off the Trophy.

“Unfinished business”

Six months after this forced surrender, the CEO of ENZA(2)(2) The ENZA logo, redesigned for the Jules Verne Trophy.  made an announcement at the general assembly: “We have got unfinished business; we’ve got the equipment and the crew, and we certainly have the will to finish the job.”

made an announcement at the general assembly: “We have got unfinished business; we’ve got the equipment and the crew, and we certainly have the will to finish the job.”

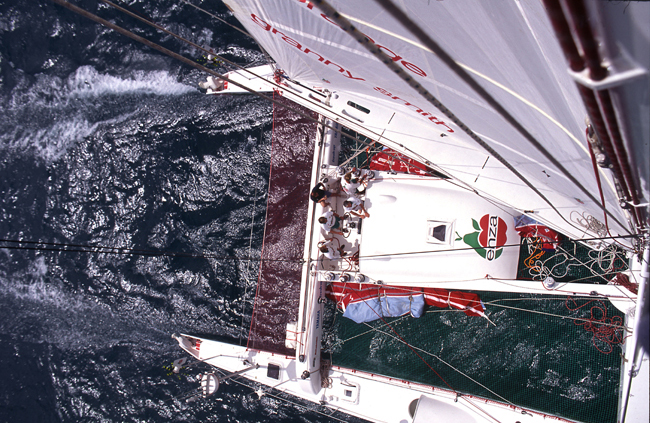

Repaired in the McMullen & Wing yard in Auckland, and reshaped for the race, the “big cat” now measured 28 meters. Its hull was reinforced under its waterline, its yachts had been resized, its structure lightened.

For their second attempt, Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston recruited six men(3)(3)  Ed Danby, Don Wright, David Alan-Williams and cameraman George Johns would be backed up by two new crewmembers, Barry Mackay and Angus Buchanan.The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton. Photo Philippe Millereau © Agence DPPI, instead of four their first time round.

Ed Danby, Don Wright, David Alan-Williams and cameraman George Johns would be backed up by two new crewmembers, Barry Mackay and Angus Buchanan.The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton. Photo Philippe Millereau © Agence DPPI, instead of four their first time round.

Their objective was simple: to finish the course, naturally, but also to better the time of Commodore Explorer and to establish a new world record.

This year again, they would not be the only ones taking up the challenge. Olivier de Kersauson was back, on the trimaran Lyonnaise des Eaux Dumez, also amongst the world’s biggest multihulls.

Leading the way to the equator

ENZA set the tone from the very first day, covering 411 miles (761 km) in the space of 24 hours, at an average of 17.5 knots. The Gulf of Gascony was crossed in a single day. Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston kept up the pace.

Lyonnaise des Eaux Dumez was spotted from time to time shortly after the departure, but Olivier de Kersauson kept silent most of the time, only giving his adversary a few scanty clues on his progress.

The trimaran of “ODK” reached the equator around nine hours after ENZA. Ahead of schedule, Blake and Knox-Johnston reached this first major geographical landmark after 7 days, 4 hours and 24 minutes at sea – in other words 39 hours less than Bruno Peyron in 1993.

For it was primarily this virtual competitor who preoccupied the New Zealander and the Brit. The distances covered by ENZA and the boat’s average speed, were continually compared with the past exploits of the first holder of the Jules Verne Trophy.

The potentially delicate Doldrums were passed through smoothly. This zone of temperamental winds near the equator was crossed at a speed of 8 to 14 knots. ENZA was 15 to 20 % quicker than in the previous year, rejoiced skipper Peter Blake.

St Helena’s influence

The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton © Photo Ivor Wilkins

The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton © Photo Ivor Wilkins

To reach the south seas, Blake and Knox-Johnston traced a westward curve – a strategy that was the opposite of the one they had followed in 1993 to go around St Helena High, the main obstacle on this leg of the trip, where they had found themselves becalmed.

With a broad reach thanks to the southeast trade winds off the Brazilian coast, ENZA was still ahead of its target time despite alternate squalls and calmness that slowed down its progression.

On 27 January, from land, Bruno Peyron expressed his confidence for his challengers: “The weather forecast is exceptional. St Helena High is well positionned. They just have to sail straight south before turning left as soon as they reach the Roaring Forties.”

Peyron’s calculations proved optimistic. At 33° 28 south and 29° 23 west, ENZA fell under the influence of St Helena. “Our current speed is 1.4 knots and the mainsail is crashing about with nothing to fill it, declared Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston in a telex from 29 January. “It is extremely frustrating to see all our good progress being dissipated, but there is nothing we can do except persevere.”

Barry MacKay took advantage of the calmness to inspect the boat’s hulls – a whale had crashed against the starboard a few days previously – and Don Wright climbed the mast to inspect the rigging and gear up for the Roaring Forties.

“This things you put in drinks…”

Albatrosses soon welcomed ENZA to the Great South. “We’ll go to 45°South before leveling off. It’s getting colder and bumpier by the hour but anything is preferable to sitting in light airs and watching you competition get away from you,” warned Peter Blake, on 3 February.

Going down south also helped to reduce the distance for getting around Antarctica. On the other hand, the risk of growlers or other icebergs springs up whenever the water temperature drops below 2°C. Just as sailors traditionally avoid pronouncing the word “rabbit” while at sea, the word “iceberg” was banned from the catamaran. “Peter, have you seen one of these things you put in drinks to cool them ?”, the question would come from the HQ of ENZA New Zealand.

On 5 February, ENZA went across the longitude of the Cape of Good Hope(4)(4)Ushuant-Cape of Good Hope: 19 days, 17 hours, 53 minutes and 9 seconds., with a day’s lead on the record holder. A west-southwest wind was blowing, revving up to 40 knots (74 km/h) and stirring 10-meter-high waves.

“We’re going like a train,” reported Peter Blake, “It’s wet, sunny, cool and windy and one heck of a ride. The boat is more like a submarine than a yacht most of the time and nobody has had much sleep in the last 48 hours. But we are doing very good miles and once we are through this particular system, we should be in for some real, pleasant Southern Ocean sligh rides for a change. ”

Angus in the mine, Blake in bed

Three days later, the skipper was more keyed up: “We had an incident.” ENZA had just had a close call and almost capsized. The boat “went down the mine” and “ploughed,” plunging the bow of the floats underwater, transitioning from 25 to 0 knots in just a few seconds. The off-duty crew-members were ejected from their bunks. Angus Buchanan, the youngest crew-member, who was at the helm, earned the nickname of “the miner.” As he was also the doctor on board, it was he who massaged a worked-up Peter Blake, bedridden due to backache caused by the jolt.

This incident proved to the ENZA’s skippers the utility of an eight-person-strong crew. Even with one quarter of the team down, there was no slacking of pace.

The catamaran’s performance was no longer affected by the bad weather. Since entering the Indian Ocean, the boat’s average speed had gone up to 16.57 knots. ENZA extended its lead over its phantom competitor, Commodore Explorer, and left Lyonnaise des Eaux Dumez, its direct adversary, over 1,400 miles (2,592 km) behind.

“Be careful boys,” advised Florence Arthaud over the radio. The co-founder of the Jules Verne Trophy had come to encourage the Anglo-Saxon team: “We’re crossing our fingers and thinking of you. But don’t go too fast all the same – we’re counting on trying our luck after you!”

Peter Blake, bedridden due to backache keeps on looking for the best route. The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton. Photo George Johns © Agence DPPI

Peter Blake, bedridden due to backache keeps on looking for the best route. The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton. Photo George Johns © Agence DPPI

“It’s nice for penguins”

On 21 February, at 59°43 south and 175°53 east, ENZA finally managed to head east. Sailing along the bottom of the world, the catamaran skipped along at an average of 20 knots, destination Cape Horn. On the previous day, Southern Lights had pierced through the night. “A good omen for the rugby,” hoped the English on board. On land, the Five Nations Championship was being played out.

At sea, the duel with Olivier de Kersauson picked up again. While the low latitudes in which ENZA was sailing meant that the longitudes were being swallowed up more quickly, the winds accompanying the boat were irregular. Four successive lows blocked the Kiwi catamaran in the south while the French trimaran, sailing further north, pulled off better averages.

On board ENZA, living conditions were rough at 61° south. Inside, the heating had broken down. On the deck, water froze in bottles. “It’s nice or penguins but not for humans,” commented Peter Blake.

A watchman was permanently stationed at the boat’s bow. The Kiwi skipper would later tell of coming across “great cathedrals of sculpted ice”. “Some of which we measured by sextant to be a mile across and as much as 200ft high”, said Peter Blake.

The return of Kersauson

45th day of sailing. After the agony of the Pacific Ocean, it was a northeasterly storm that would again test the crew and the boat as they approached Cape Horn. The rigging was malingering, the genoa was torn: ENZA was taken off course to allow for emergency repairs. Precious miles were lost.

On 5 March, Peter Blake finally went around Cape Horn, for the fifth time, after 48 days at sea. On board, only two crew-members were seeing the Horn for the first time.

ENZA left the Pacific with a five-day lead on Commodore Explorer. But Kersauson was close behind. Twenty-six hours after Blake and Knox-Johnston, he also cleared Drake’s passage.

The trip up the Atlantic, along the coast of Brazil, had penalized Bruno Peyron and his crew. Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston chose to travel further east. The intention was to avoid head wind and a close-hauled ascent, hard-going for a racing catamaran. ENZA’s average speed fell to 8 knots. The two skippers would have to wait 10 days to see if their option paid off. On 14 March, at 25°51 south and 23°54 west, ENZA finally found the southeast trade winds on its course.

Trailing behind for 50 days, Lyonnaise des Eaux Dumez suddenly emerged at the same latitude… But the French crew had three fewer men than their opponents. Fatigue would soon reap its effects.

And those on board ENZA were also impatient to arrive.

Home stretch, last storm

“The convergence zone(5)(5)Intertropical Convergence Zone or Doldrums. currently is a 2 degrees north so tonight and tomorrow are going to be very interesting for La Lyonnaise. We seem to have got away. All the signs are good but we’ve still got our finger crossed !” wrote Peter Blake in a morning telex, on 21 March. The conducive weather conditions at the exit of the Doldrums also worked to the advantage of Lyonnaise des Eaux Dumez.

2,208 miles (4,089 km) from the arrival, on 24 March, ENZA had to keep up an average of over 7.5 knots if its skippers were to take the Trophy off Bruno Peyron. Given the speed that had been maintained from the start, it was doable. But weather is not always predictable. And the Azores High is a major obstacle that needs to skirted in the northern hemisphere, at the risk of being stuck with an immobilized boat a few thousand miles from Ushant. The thing was, there were only 12 days 6 hours and 15 minutes left for Blake and Knox Johnston to win their wager.

On 27 March, Olivier de Kersauson broke his silence: Lyonnaise des Eaux Dumez, 640 miles (1,185 km) behind ENZA, at 32°27 north and 48°35 west, had suffered rigging damage and was slowed down by the weak winds generated by the Azores High.

The New Zealander catamaran also struggled with these weather conditions, dropping down to 5 knots, before picking up speed again, still far ahead of the French.

Hawsers behind ENZA. The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton. Photo Henri Thibault © Agence DPPI

Hawsers behind ENZA. The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton. Photo Henri Thibault © Agence DPPI

Two days from arriving, it was tempting to release the “big cat” and let ENZA hurtle to victory. But the two skippers remained prudent. The boat was tired, the men as well.

The last miles were grueling, the sea was choppy, the wind climbed to 70 knots (129 km/h) off Brittany. “As bad as Cap Horn,” Blake would remark later. ENZA rushed on and threatened to capsize. It was necessary to drop hawsers behind them to keep control of the boat.

Again tossed by a storm off Ushant, the crew-members of ENZA New Zealand crossed the finish line of the Jules Verne Trophy on 1 April 1994, recording a time of 74 days, 22 hours, 17 minutes and 22 seconds for its circumnavigation. Bruno Peyron’s record had been beaten by almost 5 days.

“ENZA New Zealand is a remarkable vessel, ad it was a fantastic learning curve in seamanship,” declared Peter Blake to the press.

“With a new boat and a bit of luck a 67-days circumnavigation is possible,” foretold the Kiwi skipper, before adding: “But it won’t be me.”

Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston had attained their objective. They were already dreaming of other challenges.

But Olivier de Kersauson hadn’t yet spoken his last word.

Sir Peter Blake and family, in Brest. The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton. © Agence DPPI

Sir Peter Blake and family, in Brest. The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton. © Agence DPPI

30 January 1993. Peter Blake, Robin Knox-Johnston and French skipper Bruno Peyron look at the last weather forecasts some hours before starting from Brest. Sir Peter Blake Trust of NZ © Christian Février

30 January 1993. Peter Blake, Robin Knox-Johnston and French skipper Bruno Peyron look at the last weather forecasts some hours before starting from Brest. Sir Peter Blake Trust of NZ © Christian Février Commodore Explorer’s dream team : Marc Vallin, Jacques Vincent, Bruno Peyron, Cam Lewis, Thomas Coville (who was not onboard Commodore Explorer during this attempt for the Jules Verne Trophy), Olivier Despaigne. © Photo Jacques Vapillon.

Commodore Explorer’s dream team : Marc Vallin, Jacques Vincent, Bruno Peyron, Cam Lewis, Thomas Coville (who was not onboard Commodore Explorer during this attempt for the Jules Verne Trophy), Olivier Despaigne. © Photo Jacques Vapillon. © Photo Christian Février

© Photo Christian Février

Commodore Explorer over the finishing line of the Jules Verne Trophy, not far from Ushant © Photo Christian Février

Commodore Explorer over the finishing line of the Jules Verne Trophy, not far from Ushant © Photo Christian Février