Five years after Bruno Peyron’s historic performance, it was Franck Cammas’ turn to challenge the chronometer on the three oceans with his team. The goal: a circumnavigation in under 50 days. The young skipper had met with setbacks on his first two attempts at the course. From dead calm to sudden sprints, his third try would lead him to victory.

2004: Groupama announced the creation of a gigantic trimaran aimed at beating historic sailing records, and to cap them all, the Jules Verne Trophy(1)(1)Le Monde en 48 jours, Luc Le Vaillant, Dominic Bourgeois, Yvan Zedda, Mer&Découverte Editions, 2010..

The schedule targeted by the sponsor was tight – this was the first challenge to be met. Marc van Peteghem and Vincent Lauriot-Prevost were set the task of designing the new prototype in a year and a half, and the boat constructor Multiplast – source of most of the Trophy’s winners – had the job of building it.

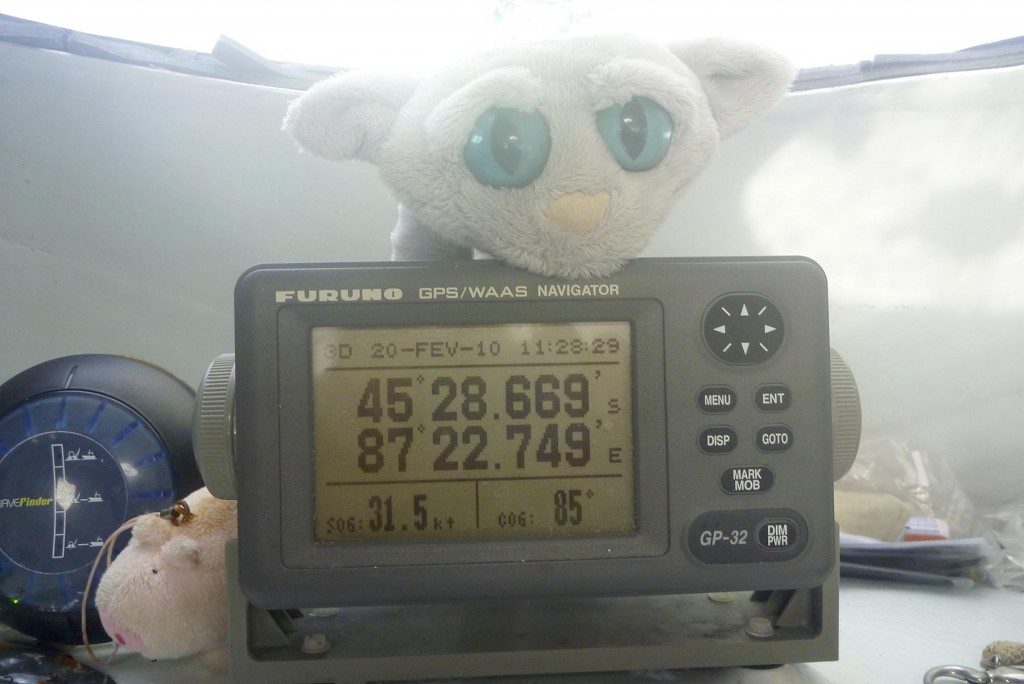

As of June 2006, Groupama 3 was ready. It was a 31.5-metre-long trimaran, shorter than the maxi catamarans that had been running on the circuit for almost a decade, but also lighter, more reactive, and easier to steer for ten crewmembers, operating on shifts of three on deck.

The Groupama champion, Franck Cammas, was already a whizz at competitive sailing. And even if he had never affronted Cape Horn and knew nothing about the southern seas, he could rely on his crewmembers(2)(2)Team: Franck Cammas, Fredéric Le Peutrec and Stève Ravussin (shift managers); Lionel Lemonchois, Loïc Le Mignon and Thomas Coville (helmsmen); Ronan Le Goff, Jacques Caraës and Bruno Jeanjean (bowmen) and Stan Honey (navigator). Sylvain Mondon from Météo France for land-based routing. who, between them, had notched up thirteen world tours, four of them already having been on winning Jules Verne Trophy teams: Thomas Coville with Olivier de Kersauson in 1997; Jacques Caraës, Ronan Le Goff and Lionel Lemonchois, with Bruno Peyron in 2002 and 2005.

After a vigorous warm up – the setting of four records in the Atlantic(3)(3)Discovery Route, May 2007: 7 days, 10 hours, 58 minutes and 53 seconds; Miami-New-York, June 2007: 1 day, 11 hours, 5 minutes and 20 seconds at an average of 27 knots; distance covered in 24 hours, July 2007: 794 miles at an average of 33.08 knots; and Atlantic crossing, July 2007: 4 days, 3 hours, 57 minutes, 54 seconds at an average of 28.65 knots. and another in the Mediterranean(4)(4)Crossing of the Mediterranean, May 2009: 17 hours, 8 minutes, 23 seconds, at an average of 26.4 knots. – Groupama 3’s ten crewmembers set off in pursuit of the Jules Verne Trophy. Twice, they were forced to give up even though Groupama 3 had sped ahead of Orange II and beaten a few intermediary records. On 18 February 2008, the trimaran capsized off New Zealand. On 29 December 2009, a float cracked off South Africa and the damage was impossible to repair at sea.

The disappointment was immense. Cammas’ men knew that they would go out again soon enough, but not without an element of apprehension.

26th of April 2008, Groupama 3 arrives in Lorient, with its float cracked during a first attempt. ©Yvan Zedda / Groupama Team

26th of April 2008, Groupama 3 arrives in Lorient, with its float cracked during a first attempt. ©Yvan Zedda / Groupama Team

Winning wager

The third departure was abrupt. Groupama 3 crossed the Ushant-Point Lizard line on 31 January 2010, at 13 hours, 55 minutes and 53 seconds (GMT). The weather conditions had not been very engaging so far that year. It was necessary to take advantage of an optimal slot – even if far from ideal – to get to the equator in under a week and make the most of a welcome depression off Brazil. It was a wager to try and make this sequence, for there is no certainty in forecasts for periods further than a week away.

©Yvan Zedda / Groupama Team

©Yvan Zedda / Groupama Team

The first and main uncertainty was removed when the Spanish tip of Cape Finisterre was rounded in less than 24 hours. “We’re sailing with a gennaker and mainsail on a calm sea that allows us to slide along well,” rejoiced Franck Cammas on 1 February. “We’ve managed to clear the delicate passage north of Cape Finisterre where we really couldn’t afford to be late, at the risk of being blocked by an anticyclone: the first barrier is behind us!”

Afterwards, Groupama 3 progressed quickly thanks to the trade winds, then managed to pull through a prolonged halt in the stillness of the Doldrums. The equator was crossed in 5 days, 19 hours and 7 minutes, in other words 3 hours and 44 minutes less than the best time set on this section of the itinerary by… Groupama 3, in November 2009!

Bubbles

Groupama 3 kept up an average of 22 knots since departing from Ushant, and sped along to gain a day’s advance on the holder of the Jules Verne Trophy. The only hitch was that Saint Helena’s High, the main barrier in the south Atlantic, stretched a broad calm zone over a very high latitude. Cammas and his men were forced to skirt the phenomenon by nearing the Brazilian coastline. The trimaran’s speed did not drop – Groupama 3 often reached peaks topping 30 knots – but this detour to the west lengthened its course.

The ten crewmembers attempted to get through on a byway on their ninth day at sea. No luck. Trapped, they would need to wait for a depression from the South American coast – one that that failed to come. Things didn’t improve when Saint Helena’s High dispersed, scattering anticyclone bubbles along the boat’s path. On the twelfth day at sea, the virtual Orange II passed in front of Groupama 3. At 37 degrees South, the winds are always unstable, and the trimaran’s average speed dropped to between 8 and 14 knots.

Groupama 3 finally found wind again off the Tristan da Cunha islands, at the longitude 12°19 West, and suddenly scurried at 35 knots on a flat sea. Destination: the most dreaded ocean on the course.

Stève Ravussin and Thomas Coville. ©Groupama Team

Stève Ravussin and Thomas Coville. ©Groupama Team

Brake and acceleration

Cammas’ trimaran was only seven and a half hours behind Orange II when the Cape of Good Hope was rounded. Then, on 15 February, after 14 days, 15 hours and 47 minutes at sea, the crew went past Cape Agulhas that marks the entrance into the Indian Ocean.

Waiting for a good northerly air stream, the ten crewmembers were forced to slow down. The drop in speed was typical of this world tour in stops and starts: the wind weakened to under 10 knots (18 km/h) and the boat’s speed fell to 20 knots. Groupama 3 fell into another trap and tried to escape by changing course, again and again.

“The weather systems are taking us on quite a northerly course,” specified Franck Cammas on radio, on 17 February, at 42°South, “but it’s not a bad thing for avoiding the icebergs near the Kerguelen Islands. We haven’t taken the risk of going further south as we might find ourselves with a depression portside, with winds against us, and that’s no good at all! But our choice forces us to keep up high averages to stay in this good system.”

On the seventeenth day of sea, Groupama III lagged behind Orange II by 338 miles (719 km).

©Groupama Team

©Groupama Team

The wind that the ten crewmembers had been hoping for since entering the Indian Ocean reached Groupama 3 three days later, to the south of the Crozet Islands. The speedometer showed peaks of 35 knots, and an average speed of 30 knots. The course was finally straight, along 45°South, towards Tasmania, with a west-northwesterly wind of around twenty knots.

The trimaran soon went over the longitude of Cape Leeuwin, and scored, on the night of 22 February, its first benchmark time on this third attempt at the Jules Verne Trophy: Cape Agulhas-Cape Leeuwin, in 6 days, 22 hours and 34 minutes.

Orange II’s challenger now only had a four-hour lag to catch up. The sea was orderly, the wind stable and regular, blowing at 20 knots (37 km/h) from the northwest. Cammas’ crew left the Indian Ocean under a star-studded sky, the Southern Cross overhead.

Neck and neck

The record for crossing the Indian Ocean was beaten on 23 February, in 8 days, 17 hours and 39 minutes. Groupama 3 once again bettered the Jules Verne Trophy reference time “We’re following our progress by comparing ourselves with Orange II. Even if it’s not our direct competitor, we’re looking at its virtual traces,” declared shift manager and helmsman Frédéric Le Peutrec on the daily radio session. “We knew that the leg under Australia would let us make up for our lost time because Bruno Peyron and his crew had to make several jibes with phases of slowdown. But they crossed the Pacific very quickly… It’ll be difficult to keep up the average up to Cape Horn.”

The advance on the performance of Bruno Peyron’s catamaran was still slim: 200 miles (370 km) at the entrance of the world’s largest ocean. It was now necessary to go south to shorten the route to Cape Horn – the reasoning being that latitude degrees file by more quickly closer to the Antarctic where the meridians are closer to one another.

On 25 February, the ten crewmembers hit the midway mark. They were progressing well at 50 degrees South and continuing to swallow up the miles. But on 27 February, a cold front caught up with Groupama 3, forced at that point to gibe twice on its way to the mythical cape.

©Groupama Team

©Groupama Team

At 55°South, while approaching Horn, the sea turned rough, the cold became sharper. The conditions deteriorated from hour to hour. Facing a chaotic swell and violent squalls, the trimaran hurried north-northeast to dodge a disturbance hurtling along at 45 knots along its course. And also to avoid an ice field. On the twenty-eighth day of sailing, winds at 80 knots (145km/h) rushed into Drake Passage, between the tip of South America and the Antarctic continent – before the wind fell and turned north, three days later, while Groupama 3 was in sighting distance from the Chilean coastline.

Finally rounding Cape Horn on Thursday 4 March at 18 hours and 30 minutes (GMT), Groupama 3 allowed Orange II to maintain its Pacific crossing record of 8 days, 18 hours and 8 minutes by 59 minutes. The trimaran nonetheless kept its advance of 175 miles (324 km) on the giant catamaran’s performance. The race was tight.

©Groupama Team

©Groupama Team

Laborious Atlantic

It was the first time that Franck Cammas saw Cape Horn while Thomas Coville was celebrating his seventh passage of the celebrated cape. “Even for the most blasé, it’s still a very great moment,” said the helmsman on the radio, on 6 March. “Above all, it’s an important transition, it’s a focal point, all the more because this time we had to wait a long time for it! Now we’re entering a different logic in the course, which becomes a race against the clock: it’s time to really go for it and beat the record.” Coville, like the other Groupama 3 crewmembers, still believed that the Jules Verne Trophy was possible, even if the climb up the Atlantic promised to be laborious.

Groupama 3, entering the Atlantic upwind while Orange II had taken advantage of downwind conditions, traced a very easterly curve, thus lengthening its return journey. As of the thirty-fifth day at sea, the advance on Bruno Peyron’s catamaran was lost. The weather worsened. Groupama 3 continually had to adapt its course and speed to match the brutal and unstable conditions: anticyclone bubbles and opposing wind off Uruguay; storms alternating calmness and violent squalls off Brazil. Cammas’ crew feared that the boat would break apart. “We didn’t expect that this phase of strong wind would be so long! The bad weather with 35-37 knots (64-68 km/h) was only meant to last 4 hours at 10 a.m. on Tuesday. In fact, it lasted four hours longer, rising up to 42 knots (78 km/h) with heavy seas,” reported Loïc Le Mignon on 10 March.

To get to the equator as quickly as possible, Groupama 3 had to avoid nearing the Brazilian coast – at the risk of falling into a calm zone – and had to refrain from going out too far to sea where the northeasterly wind would compromise its progress.

When the Earth’s longest parallel was crossed on 14 March, after 41 days, 21 hours and 9 minutes at sea, Groupama 3 was 405 miles (750 km) behind Orange II, in other words, a little more than a day of sailing. The distance was almost discouraging, but the ten crewmembers hoped to see it melt in the northern hemisphere.

©Groupama Team

©Groupama Team

Final sprint

Once over the equator, there were only 8 days and 19 hours left for the Groupama 3 men to get to Ushant on time. Bruno Peyron had spent 9 days, 11 hours and 15 minutes on finishing this last stage in 2005.

“Thankfully, Groupama 3 is comfortable with short timeframes,” Franck Cammas said with confidence on 14 March. Thankfully for the skipper, his luck was about to change, along with the wind. The trimaran managed to quickly latch onto the brisk trade winds off Cape Verde. On 16 March, Groupama 3 again hopped ahead of its virtual competitor. The ten crewmembers were ready for the first obstacle: the Azores High and its barrier of weak winds. Sylvain Mondon, the land-based router, also announced a series of low-pressure fronts whose potential should be maximized for rushing to Ushant.

On 17 March, as a southwesterly disturbance flowed, Franck Cammas and his nine crewmembers positioned themselves in front of a cold front. “We’ve latched onto the system that’s on the way right up to Brittany. If we have no technical problems, then we have nothing more to fear on the meteorological front. We’re on the last wind train that’s going right up to the arrival point,” announced Fred Le Peutrec on the daily radio session.

But this last stretch would not be run on rails. Franck Cammas and Stan Honney, the navigator on board, planned a series of gibes to bring the boat to the south of the depression, in order to spare it from too much disturbance. At 1,500 miles (2778 km) from Ushant, the wind became more unstable, switching from southwest to northwest. The crewmembers set in motion a series of maneuvers. The boat, tired by its high-speed world tour, bounced on the waves. But more speed was needed despite the risk of breakage, for a high-pressure ridge was emerging on the trimaran’s coattails.

It was in the middle of the night, on 20 March, that Franck Cammas and his nine crewmembers crossed the arrival line of the Jules Verne Trophy, under the flashes of the Créac’h, Ushant’s monumental lighthouse. They had just finished their world tour via the three capes in 48 days, 7 hours, 44 minutes and 52 seconds, beating the circumnavigation speed record. Going under the symbolic bar of 50 days, they also notched up the bonus of an absolute record on the last stretch of the course: the north Atlantic, swallowed up in 6 days, 10 hours and 35 minutes.

Beaten by 2 days, 8 hours and 35 minutes, Bruno Peyron, skipper of Orange II in 2005, congratulated all his happy challengers – the crewmembers, the land, technical and weather team, the architects, the sponsor. “All deserve this methodically constructed success. Together, they have written a beautiful new page in the history of the Jules Verne Trophy. I’m proud to have been beaten by the best ocean multihull team today, and I’m looking forward to relaunching our team to ‘recover’ the title.”

Groupama 3 in Brest after 48 days, 7 hours, 44 minutes and 52 seconds at sea. ©Yvan Zedda / Groupama Team

Groupama 3 in Brest after 48 days, 7 hours, 44 minutes and 52 seconds at sea. ©Yvan Zedda / Groupama Team

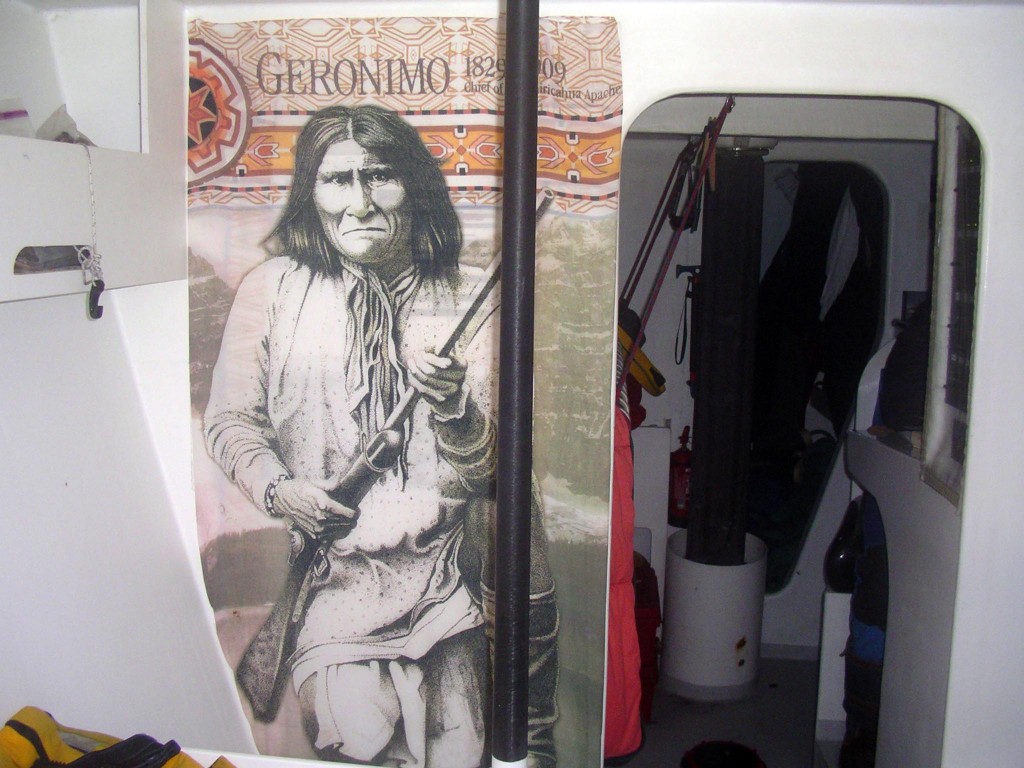

Encouragment on the starting line.“Eat indian twice rather than once” is written on the sign, refering to Geronimo and Cheyenne, the two vessels Bruno Peyron has decided to challenge. ©Photo Jean-Baptiste Epron

Encouragment on the starting line.“Eat indian twice rather than once” is written on the sign, refering to Geronimo and Cheyenne, the two vessels Bruno Peyron has decided to challenge. ©Photo Jean-Baptiste Epron © Photo Jacques Vapillon

© Photo Jacques Vapillon

©Photo Jean-Baptiste Epron

©Photo Jean-Baptiste Epron ©Photo Jean-Baptiste Epron

©Photo Jean-Baptiste Epron

©Photo Jean-Baptiste Epron

©Photo Jean-Baptiste Epron © Photo Jacques Vapillon

© Photo Jacques Vapillon

Archives Rivacom

Archives Rivacom Didier Ragot and Xavier Douin. Archives Rivacom

Didier Ragot and Xavier Douin. Archives Rivacom Archives Rivacom

Archives Rivacom Archives Rivacom

Archives Rivacom Archives Rivacom

Archives Rivacom