“At the edge of the Antarctic, we’ll glide around the world. We’ll go surfing in those places where, since Cook, few have ventured, crossing the seasons from west to east, leaving from Ushant and then back again, passing through the Capes of Good Hope, Leeuwin and Horn. We’ll count down the days, we’ll hurtle down the slopes, we’ll swallow up the meridians. The voyage will last just eighty days, just enough time for a small tour.”

Florence Arthaud

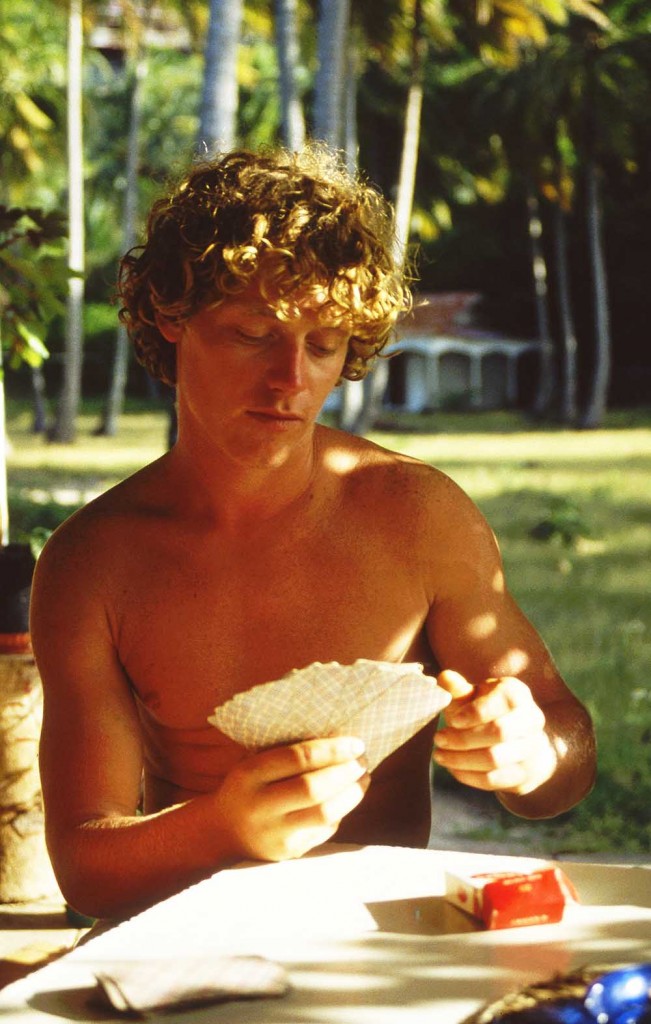

“And what if we went around the world in 80 days?” It was Yves Le Cornec, also known as “Mickey”(1)(1) Yves Le Cornec in the Iles des Saintes archipelago after the Route du Rhum, 1982. © Photo Christian Février , who tossed up the idea, one evening in 1985, at a table of merry-making sailors at the home of the good doctor Jean Le Rouzic in Trinité-sur-Mer in Brittany. Along with Mickey, there was Florence Arthaud, Eugène Riguidel, Gabriel Guilly and their band of friends, celebrating their return from a transatlantic trip from Québec to Saint Malo. On board the William Saurin trimaran under Riguidel, they had covered 3,000 miles at around 13 knots – an average speed that at that time had never been reached when crossing the Atlantic. “While talking and imagining circumnavigations of the globe at this speed, the idea of 80 days suddenly stood out as obvious to me,” recalls Yves le Cornec.

Yves Le Cornec in the Iles des Saintes archipelago after the Route du Rhum, 1982. © Photo Christian Février , who tossed up the idea, one evening in 1985, at a table of merry-making sailors at the home of the good doctor Jean Le Rouzic in Trinité-sur-Mer in Brittany. Along with Mickey, there was Florence Arthaud, Eugène Riguidel, Gabriel Guilly and their band of friends, celebrating their return from a transatlantic trip from Québec to Saint Malo. On board the William Saurin trimaran under Riguidel, they had covered 3,000 miles at around 13 knots – an average speed that at that time had never been reached when crossing the Atlantic. “While talking and imagining circumnavigations of the globe at this speed, the idea of 80 days suddenly stood out as obvious to me,” recalls Yves le Cornec.

The day after the dinner, Mickey picked up a calculator and pored over a map of the world. The figures said it was possible: at an average speed of 12.8 knots, 26,000 miles could be covered in 80 days minus 5 minutes. The literary wager launched, in 1872, by Jules Verne to his phlegmatic character Phileas Fogg offered an elegant pretext for a new oceanic adventure. But the Jules Verne Trophy was not yet born. “At the time, we were still very far off from imagining the performance of boats today, and pulling off a circumnavigation at that speed represented a real challenge,” explains the trophy’s inventor.

One challenge after another

The enthusiasm of sailors – and above all, their sponsors – was not piqued until Titouan Lamazou’s highly publicized 1990 victory in the Vendée Globe, designed as the ultimate race to open the decade. Titouan, winner of the competition’s first edition, sailed solo around the world, without assistance or stopovers, in 109 days, 8 minutes and 48 minutes. “The way I see it, winning a supreme victory is not an end in itself,” the champion told the newspaper Libération. “One challenge will replace another; the eighty-day challenge was waiting for us behind the port’s jetty.”

Also in 1990, Florence Arthaud became the first woman to win a singlehanded ocean race, the fourth edition of the Route du Rhum.

The two sailing stars of the year came up with the idea of founding a new challenge that would perpetuate the tradition of major round-the-world ocean races. They wanted the Jules Verne Trophy to follow in the footsteps of the Golden Globe Challenge inspired by Sir Francis Chichester in 1968; the BOC Challenge, created in 1982 by Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, winner of the Golden Globe; and the Vendée Globe Challenge, launched by Philippe Jeantot, winner of the two first editions of the BOC. The two French sailors also bore in mind the first crewed ocean race to circumnavigate the globe: the Whitbread, whose saga began in 1972, and which would seal the legends of navigators including Peter Blake, Robin Knox-Johnston and Éric Tabarly.

On 29 January 1991, Florence and Titouan created the “Tour du Monde en 80 Jours,” a non-profit association that would support the Jules Verne Trophy. In this way, they promised to bring to life Yves Le Cornec’s wonderful idea, and above all, to make it endure beyond a single exploit under the eighty-day mark.

Free rein

In an era when most race regulations placed limits on vessel size, the promoters of the Jules Verne Trophy imagined a competition open to any yacht, with no restrictions on boat or crew size. It was thought at that time that the available racing boats were not powerful enough to match Phileas Fogg’s record.

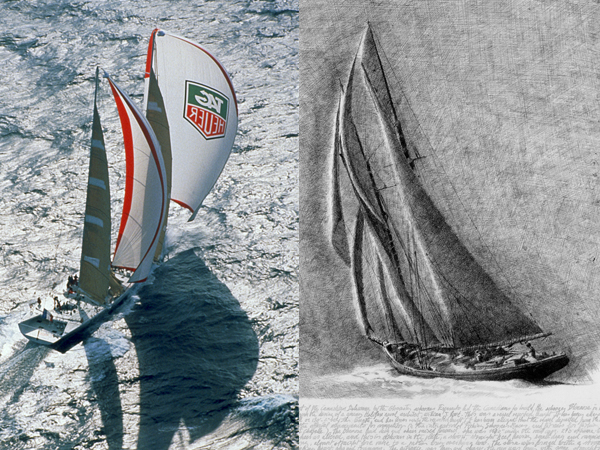

Titouan Lamazou soon put all his efforts into creating a gigantic monohull capable of meeting the challenge. He readily saw himself as an heir to Rudyard Kipling’s Captain Courageous, at the helm of cod-fishing schooners that would crisscross the Grand Banks of Newfoundland in the 19th century until the dawn of the 20th century. His Tag Heuer, 44 meters long, would be the descendant of the Bluenose – also 44 meters – a mythical Canadian schooner that, for years, dominated the Fisherman’s Trophy invented by Sir Thomas Lipton for this type of boat, and that marked the golden age of Western “working” sailing.

While Titouan fine-tuned the new Bluenose, Florence Arthaud endeavored to obtain, from her sponsor Pierre Premier, financing for a forty-meter catamaran.

Titouan Lamazou’s TAG HEUER and the legendary shooner Bluenose, drawn by Titouan. ©Photo Gilles Martin-Raget

Titouan Lamazou’s TAG HEUER and the legendary shooner Bluenose, drawn by Titouan. ©Photo Gilles Martin-Raget

The eighty-day challenge was also a challenge for designers who came up with prototypes. “The Jules Verne Trophy offers new free rein to the genius of architects and builders, and will be a pretext – for many years to come I hope – for firing up the imaginations of skippers,” declared Titouan when he, along with Florence and others, laid the foundations of the new challenge.

A rendezvous with sailors

To draw up the simplest possible regulations, Titouan and Florence met up with experienced navigators, lovers of freedom who were driven by dreams resembling their own. They frequently gathered at the houseboat of Dany and Yvon Fauconnier. Moored on one edge of the Seine, on the banks of the Île de la Jatte, this was a meeting spot for sailors in Paris. Also with them were the ever-loyal Jean-François Coste, Yves Le Cornec, Eugène Riguidel, Jean-Yves Terlain, but also, for this purpose, Philippe Monet and the Peyron brothers.

It was namely here that the itinerary of their world tour was sketched out: with no assistance and no stopovers, the crews would sail from east to west, on the open sea, passing three capes to the portside: Good Hope, Leeuwin and Horn. At the departure and at the finish, they would go over an imaginary line at the entrance of the English Channel, between the UK’s Lizard Point and France’s Ushant Island(2)(2) The Créac’h lighthouse of Ouessant, one of the two ends of the Jules Verne Trophy departure line. © Photo Christian Février .

The Créac’h lighthouse of Ouessant, one of the two ends of the Jules Verne Trophy departure line. © Photo Christian Février .

The Jules Verne Trophy was placed under the High Patronage of the French Ministry of Culture. It was created following a call for tenders financed by the ministry, won by US artist Tom Shannon. The original sculpture remains the property of the French State and is conserved in the Paris Marine Museum. The Trophy would be presented to the skipper who beat the circumnavigation speed record in under 80 days. And its holder would in turn hand it over to whoever bettered his or her record.

Verne, Blake and Knox-Johnston(3)(3) Sir Peter Blake and Sir Robin Knox-Johnston on the doorstep of the Yacht Club de France. The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton.

Sir Peter Blake and Sir Robin Knox-Johnston on the doorstep of the Yacht Club de France. The Sir Peter Blake Trust Collection / Alan Sefton.

Florence and Titouan headed to Portsmouth to present the “Jules Verne” to Peter Blake. The winner of the Whitbread dreamed of a new challenge to fill out one of the most prestigious prize lists in the world of sailing. “For those tempted by adventure, it’s becoming more and more difficult to be first. There aren’t many more mountains left to climb; very few challenges remain that deserve being called records, and that can bring us personal satisfaction,” regretted the New Zealander skipper. The Jules Verne Trophy could however – he was convinced – “drive his adrenalin levels back up.”

“What makes this challenge so attractive is that it is possibly possible,” added his sailing companion Robin Knox-Johnston. The holder of the first non-stop, single-handed circumnavigation record (Golden Globe Challenge, 1968) was also a believer. “Mix technology in with the harsh reality of the Forties and the challenge becomes irresistible,” he continued with enthusiasm. “If we succeed, it will be the triumph of ingenuity and the human spirit.”

For Florence and Titouan, the support of these ocean-racing giants gave their challenge international legitimacy as of its launch.

Open line

The day on which the departure line was officially opened, Peter and Robin came to Paris. The solemn announcement was made, on 20 October 1992, in the lounge of the Yacht Club of France, in the 16th arrondissement. Three French ministers were present: Jack Lang, Minister of Culture, Charles Josselin, Minister of the Sea, and Frédérique Bredin, Minister of Sport. The Tour du Monde en 80 Jours association summoned the top sailors. Bernard Moitessier honored them with his presence; he hadn’t seen Robin Knox-Johnston since 1968 when both had been at the starting line of the Golden Globe Challenge…

Official launch of the Jules Venre Trophy, on 20 October 1992, in the lounge of the Yacht Club of France. From left to right : Robin Knox-Johnston, Frédérique Bredin, minister of sports, Bernard Moitessier, Florence Arthaud, Jack Lang, minister of culture, Titouan Lamazou, Charles Josselin, miniter of sea, Peter Blake and François Carn, président of the Yacht Club de France. © Photo Gilles Klein

Official launch of the Jules Venre Trophy, on 20 October 1992, in the lounge of the Yacht Club of France. From left to right : Robin Knox-Johnston, Frédérique Bredin, minister of sports, Bernard Moitessier, Florence Arthaud, Jack Lang, minister of culture, Titouan Lamazou, Charles Josselin, miniter of sea, Peter Blake and François Carn, président of the Yacht Club de France. © Photo Gilles Klein

Florence Arthaud and Titouan Lamazou informed the press that they were not ready to set sail. Titouan’s prototype would only touch the waves two months later. And Florence had no boat.

It was at that moment that Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston chose to announce their upcoming departure. The skippers from New Zealand and Britain had recently acquired the catamaran Formule Tag that they would adapt to take up Phileas Fogg’s challenge.

Bruno Peyron was not in Paris that evening, but he had already made it known that he would also be setting off at the start of 1993.

The spirit of the Trophy

It was the elder of the Peyron brothers who would be the first to set the circumnavigation speed record, finishing up in 79 days, in April 1993. Ever since, under the auspices of Jules Verne, skippers have continued to shorten the time needed to sail around the world. 74 days, then 71, 64, 63, 50, 48, and 45 days in 2012… These navigators, whose names are engraved on the base of the Jules Verne Trophy, are Bruno Peyron, three times, Peter Blake, Robin Knox-Johnston, Olivier de Kersauson twice, Franck Cammas and Loïck Peyron. Others have challenged them and will continue to do so.

The catamaran dreamed up by Florence Arthaud never saw the light of day. Titouan’s schooner sank before crossing the starting line. The two founders pursued other dreams. Florence left us too early. But a quarter of a century after the début of their joint adventure, Titouan is left with the satisfaction of knowing that the spirit of “their” Trophy remains intact. “The Jules Verne Trophy remains a reference, a prestigious emblem that honors skippers and their sponsors, and that has never swayed from this principle,” rejoices the sailor-painter.

Yves Le Cornec, the inventor of the 80-day sailing venture, also observes: “The Trophy hasn’t been hijacked. It’s stayed free of all commercial connotations and remains simple, strong and universal.”

Of course, in the space of 25 years, things have changed. Although the itinerary is the same, with Spindrift and Idec Sport sailing at over 30 knots around the globe in 2015, we’ve come a long way since the pioneering Commodore Explorer won at an average of 14.39 knots. The spirit of adventure, however, stays unshaken.

“I’d like to ask them, when they come back, how they saw the world…,” adds Yves Le Cornec. For that’s what it’s all about in the end: running to see the world.