Olivier de Kersauson / Sport-Elec

It was Olivier de Kersauson’s sixth attempt. The man from Brittany was bent on setting a new world record for speed – even at the risk of seeing Sport-Elec, his gigantic trimaran, trapped by deadly ice in the Great South. With passion and persistence, he led his crew to follow the trail of Peter Blake, determined to take the title off the last winner of the Jules Verne Trophy.

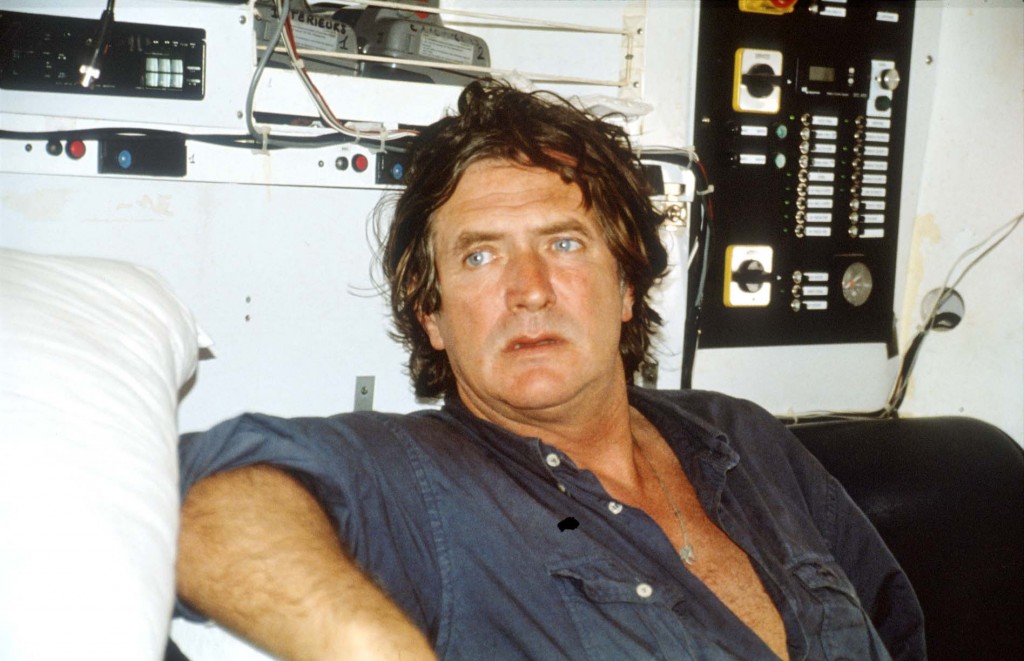

So should he turn around? Olivier de Kersauson, riveted to the chart table, lit up a cigarette with the stub of the one he had just finished. Inside the captain’s mind, a storm was raging. Outside, the sea was absolutely calm, more or less flat – and this was the way it had been ever since the boat left Ushant on 8 March 1997 at 17 hours and 37 minutes.

Kersauson had been waiting for this day for over two years. Two months earlier, on a first attempt in 1997, he had turned back when he was near Cape Town. At that time, Sport-Elec, his 27-meter-long trimaran, was four days behind his virtual competitor, ENZA New Zealand, winner of the Jules Verne Trophy in 1994(1)(1)In 1994, Olivier de Kersauson, on board the Lyonnaise des Eaux Dumez, crossed the Jules Verne Trophy arrival line, only 2 days and 6 hours after ENZA…. It was impossible, in those conditions, to beat the record established by Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston.

“Great disappointment”

Taking advantage of a brief slot when the weather was on their side, the Sport-Elec crew had just set off. But this time, if Kersauson decided to return to Ushant because of poor weather conditions, the boat would stay moored. It was already very late in the season to embark on a new attempt. The southern winter made it practically impossible to follow the optimal route that hugged the Antarctic continent. The time that had so far been lost in the North Atlantic already bode for more darkness, cold, ice, and danger by the time that they reached the Great South.

On the other side of the Atlantic, from his cottage in Maine, Bob Rice was deciphering the weather signals for the Sport-Elec crew. Olivier de Kersauson was in contact daily with this exemplary route planner who had guided Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston to their record in 1994. There was nothing encouraging about Bob’s prognostics: not a single breath of wind was expected for several days to come. “The only depression within a 1,000 mile radius was in my head,” Olivier de Kersauson later recalled(2)(2)Olivier de Kersauson, Tous les océans du monde, 71j, 14h, 22’, 8’’, Le Cherche Midi, 1997.. Already, his boat lagged behind ENZA by 1,088 miles (2,014 km).

Yves Pouillaude, Hervé Jan, Didier Gainette, Thomas Coville, Michel Bothuon and Marc Le Fur scrutinized the reactions of their captain who had turned mute.

Kersauson shot a telex to his base: “Great disappointment: we’re stuck in terrible weather and I’m afraid that we’ll make the same notoriously bad time as on our first descent / It’s enough to do your head in / Still, things could be much worse / Long live motorboats.”

Archives Rivacom

Archives Rivacom

First record

Sport-Elec crossed the equator on 20 March, at 18 hours and 23 minutes, after eleven days at sea… and finally came across some wind. The lead of the Jules Verne Trophy holder began to diminish. At around Cape Town, Sport-Elec had only gained 200 miles (370 km) on his first attempt of the year, but the lag behind ENZA was now only 580 miles (1,074 km).

When Olivier de Kersauson’s trimaran entered the Forties after 18 days of sailing, ENZA-in-1994 was still ahead of Sport-Elec-in-1997…

Olivier de Kersauson could nonetheless still rejoice in a first record at the Cape of Good Hope: a time of 10 days, 13 hours and 27 minutes for the equator-Good Hope leg.

© Photo Christian Février

© Photo Christian Février

As soon as the trimaran entered the Indian Ocean, the crew adopted a medium gennaker and a tall mainsail, in a westerly flow of 20 to 30 knots. The boat kept up a fine average of 18 knots. “Going any faster in these conditions would be perilous,” commented Kersauson. The crew started to allow itself to believe that it had a chance at the Jules Verne Trophy. Whenever they changed shifts, the same burning question was asked: how much time have we taken off ENZA? How fast?

The phantom of ENZA

Sport-Elec sped ahead with the westerly wind, darting across the Indian Ocean 430 miles (800 km) further south compared to the route traced by Blake and Knox-Johnston in 1994. The New Zealand catamaran was now only 68 miles (125 km) ahead. “The ghost of ENZA, our virtual competitor, seemed to be in view… If only we could see the boat,” remarked Kersauson.

Sport-Elec roared with the shock of waves crashing over its hull. Icy wind squealed through its rigging. On board, the men kept silent most of the time. Harnessed to the deck, bundled up in their sodden oilskins, stoic when their faces were sloshed by gallons of 2°C seawater, some were experiencing the Great South for the first time. The wind persisted in staying over 35 knots (64 km/h). Inside the boat, everything was drenched and frozen. “I’ve always hated the Indian Ocean,” said Olivier de Kersauson. “Dominique Guillet died there, Deroux as well. Between 80° and 110° East, we’re massacred in the Indian.”

At 51°South and 112°East, the Sport-Elec crew spotted the first icebergs.

Archives Rivacom

Archives Rivacom

Neck-and-neck

The Cape Leeuwin longitude was crossed on 8 April 1997 at 7 hours, 7 minutes and 3 seconds. Yet another record(3)(3)Cape of Good Hope-Cape Leeuwin in 8 days, 23 hours, 17 minutes and 3 seconds.. Sport-Elec was going faster and faster, and finally left the ghost of ENZA behind it. But not for long.

Seawater invaded the slipway and drowned the motor. The power generator was beginning to falter. Without electronics, communication with Bob Rice was no longer possible, and without routing, it was impossible to contemplate the next 15 days that they would remain in the high latitudes. Kersauson was champing at the bit. Yves Pouillaude, his second, finished repairs after three days plunged in the boat’s mechanics.

The trimaran regained its spot in front of ENZA while rounding New Zealand. The longitude of Stewart Island was crossed with a ten-hour lead on Blake and Knox-Johnston.

To the ice!

Since the descent from the South Atlantic, the weather had alternated between calm spells, contrary winds and violent squalls, but no major phenomenon had impeded the trimaran’s progress. Sport-Elec’s speed remained constant, at between 18 and 20 knots.

But soon a tropical depression blocked its way. It was necessary to go further south to avoid the storm that threatened to be a violent one. Skirting around it via the north would considerably lengthen the course, and amount to giving up the trophy. Bob Rice made it clear: there was only one solution, “to go to the ice.”

Kersauson had not shaken the memory of the float of his trimaran Charal, mutilated by a growler(4)(4)A growler is a block of ice floating between two bodies of water, far smaller than an iceberg, undetectable by radars, and difficult to see with the naked eye. during his first – aborted – attempt at the circumnavigation speed record four years earlier. “Boys, till now, we’ve been playing small-time,” warned the skipper. “Now we’re going to start on the real adventure. We’re not just racing around the world now, we’re going to the real danger.” No objections came from his crew. Their captain was secretly touched. Happy to see, at this stage of the adventure, how his men had become one, with one another and with the boat.

Hervé Jan, Thomas Coville and Marc Le Fur. Archives Rivacom

Hervé Jan, Thomas Coville and Marc Le Fur. Archives Rivacom

“It’s crazy, sometimes we have the impression that ENZA is here behind us,” reported Kersauson. “Then we realize that we’re alone, far from everything in the middle of the largest deserted stretch in the world. And in a field of mines or rather icebergs.”

Every hour, Sport-Elec would come across a block of ice as big as a building. It was impossible to go further north where an easterly wind would compromise the trimaran’s progress. But Bob Rice issued the order to go up when Kersauson led his men to the edge of the Southern Ocean, at 60°, 61° South. The authorized limit was 59° South. At this latitude, the water is at 3°C, any further south, growlers take twice as long to melt.

After three weeks in the Great South, the weather was good, the boat slid along on the surf… It was tempting to stick to the Southern Ocean and thus shorten the world tour. But the icy prison was closing in. It was time to head northeast, towards Horn.

Horn by night

Several days of storm and easterly wind combined to create a disturbed sea as they approached the cape. West southwesterly winds at 25 knots (46 km/h) blew in the opposite direction from the sea. The sea was choppy, treacherous. The wind offered no respite. For four days, Sport-Elec kept on jibing(5)(5)Change in tack (side from which the yacht receives wind) via tailwind., every four hours, and at this speed lost 130 miles (240 km) per day on the planned route.

On the night of 24 April, the trimaran rounded the Horn, 33 hours ahead of its virtual rival. The boat, in the axis of the sea and the wind, glided on at 26 knots.

The flash from the Cabo de Hornos lighthouse was the first light to be sighted by the crew in 30 days, signaling the first land since the Tristan da Cunha islands in the southern Atlantic.

“A show of courage and a fine lesson.” The message was signed Peter Blake. Another telex arrived on board, from Éric Tabarly: “You’ve offered us a spectacle of another world that will remain in sailing annals.”

Archives Rivacom

Archives Rivacom

Sudden death

But the race was not yet over. A large anticyclone blocked the Atlantic while the risk of a depression hovered in the south. There was no time to go eastwards towards Africa, to take advantage of the trade winds at the exit of the climb up to the equator. Sport-Elec had to hug the Falklands and then move up to Brazil on the western fringe of a small depression from Argentina… at the risk of finding itself caught between the coast and this depression. The miles ahead of ENZA, gained so bitterly in the Great South, would potentially be lost in no time at all.

The option that they took – the only possible one – proved to pay off initially. Kersauson soon announced 800 miles (1,481 km) and two days ahead of the record.

It was at this very moment that the board computer reserved for navigation succumbed to a sudden death. Kersauson came close to having a stroke. Yves Pouillaude knuckled down to implementing a plan B.

Apocalypse

The obligatory climb up along the South American coast brought Sport-Elec up against wavelets. The boat “stayed put,” the bow rising and falling against the sea. The rigging suffered, the men as well.

Off Uruguay, the wind suddenly shifted to 55 knots, then 60 knots (111 km/h). An apocalyptic storm swooped down on the exhausted crew. “We’re hauling everything down, MERDE!!!!” screamed Kersauson. Despite sailing with only a mast, Sport-Elec continued to speed on at 30 knots.

Back to calmness and wavelets on 1 May. The atmosphere remained highly charged. “We’ve been sailing on cobblestones for 3 days / No more storms, no sea either / We’re gliding, not quickly, not very high / ’Cos there’s no wind either / We’re tetchy on board / Fatigue,” admitted Kersauson by telex. ENZA was now only 500 miles (926 km) behind them.

Sport-Elec finally escaped the stillness of the Saint Helena High on 2 May, and began to gulp up miles running downwind. On 6 May, Kersauson’s crew crossed the equator for the second time at the 28°35 West longitude, snapping up two new records along the way(6)(6)Ushant-Equator (return) in 58 days, 13 hours and 39 minutes; and Cape Horn-Equator in 11 days, 20 hours and 41 minutes.. Yet the skipper from Brittany steered clear of crying victory.

“Good boating”

Sport-Elec extended its stay in the Doldrums – to such an extent that Kersauson saw the trophy slipping away from him. “Never mind,” he said, also quoting Tabarly: “We’ve done some good boating.” That was all that mattered.

Higher up, the Azores High formed an impassable barrier. ENZA had sailed far west of the European coastline to avoid it, but Kersauson preferred to head straight for France, at the risk of having to sail close-hauled in the north-northeasterly trade winds. Or approach the heart of the high.

But the skipper could breathe easy again on 14 May: his trimaran finally exited the calm waters, leaving the Azores islands on the port side. The boat’s average speed jumped up to 17 knots. With a three-day lead on Blake and Knox-Johnston’s performance, Kersauson and his men were now certain of taking out the Jules Verne Trophy.

The arrival was laborious. There was no final straight for Sport-Elec but tacking up to Ushant where the downdraft of a spring tide welcomed the trimaran. Sport-Elec’s crewmembers crossed the finishing line on the morning of 19 May 1997, at 08 hours, 59 minutes and 39 seconds, with the wind at 15 knots (27 km/h). The Jules Verne Trophy was theirs(7)(7) . All the boats in the world seemed to have agreed to meet to celebrate their return. Olivier de Kersauson fondly took in the string of wild islands, the bluish rock of a jagged coast, his sun-bathed Brittany. As Yves Pouillaude said jokingly: “Now we can lose our mast.”

. All the boats in the world seemed to have agreed to meet to celebrate their return. Olivier de Kersauson fondly took in the string of wild islands, the bluish rock of a jagged coast, his sun-bathed Brittany. As Yves Pouillaude said jokingly: “Now we can lose our mast.”

In Brest, Sir Peter Blake congratulates ODK and his team, the news holders of the Jules Verne Trophy © Photo Christian Février

In Brest, Sir Peter Blake congratulates ODK and his team, the news holders of the Jules Verne Trophy © Photo Christian Février

14h | 22min | 8s

1997

1997-03-11

33°24N

15°24W

1040

13

LOADING...

1997-03-30

8H30

47°15 S

18°50 E

7225

17

LOADING...

1997-04-17

21H31

57°50 S

156°05 W

14204

15

LOADING...

1997-04-25

05H36

55°47 S

65°49 W

17271

15

LOADING...

1997-05-08

13H00

07°24 N

28°39 O

310

21701

6

LOADING...

1997-05-14

13H00

31°51 N

33°37 W

23248

6

LOADING...